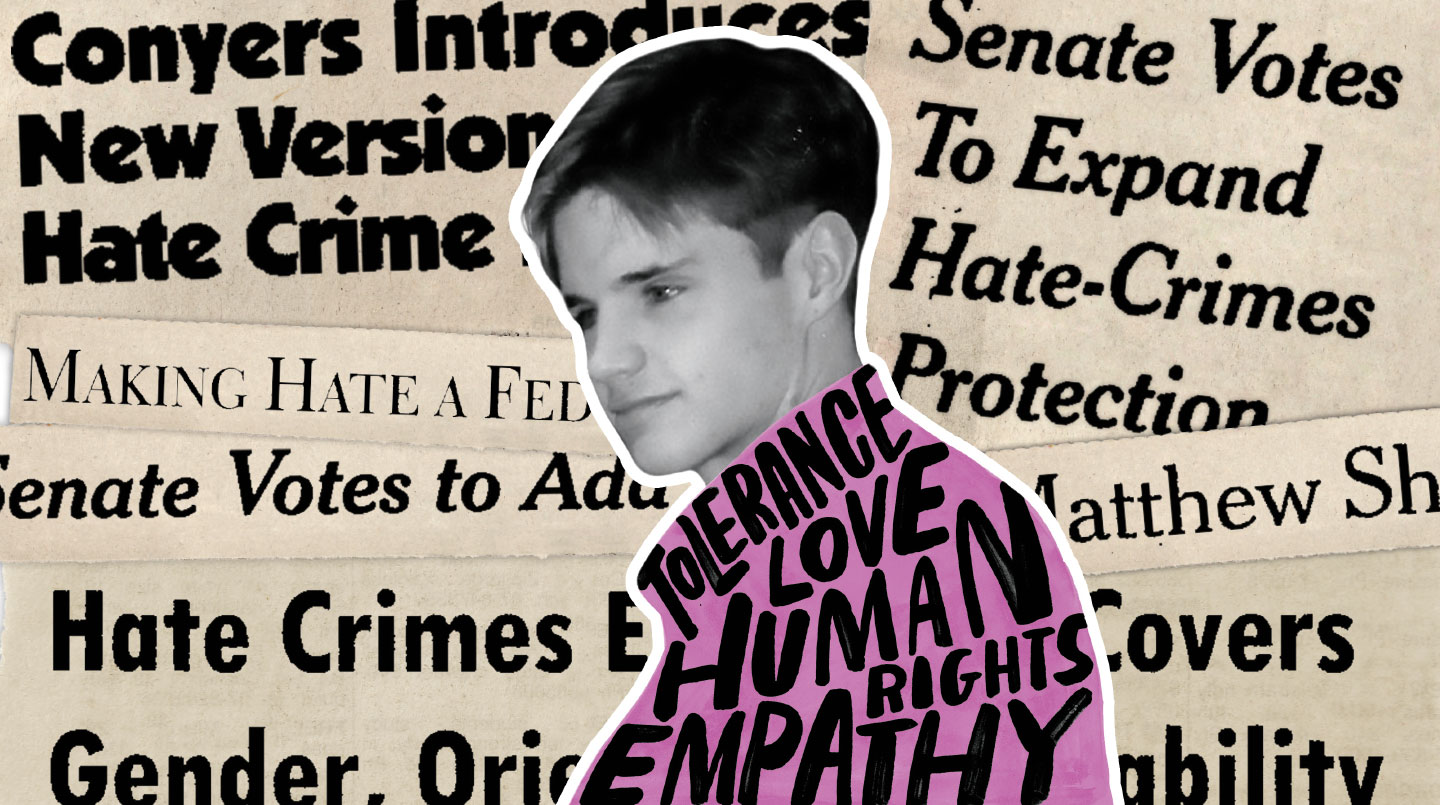

From an early age, Matthew Shepard was on a mission to make a difference in the world. At just 7 years old, he volunteered for an environmental group that was working to get his hometown of Casper, Wyoming, to start a recycling program. In the sixth grade, he played his role model, Abraham Lincoln, in a school play. And in high school, he was elected as a peer counselor because he was committed to helping others.

Shepard was also passionate about international human rights, an interest that eventually led him to study political science at the University of Wyoming in the city of Laramie. He hoped to one day work for the U.S. State Department, where he could devote his life to helping people in other countries gain the same opportunities that he had in the United States.

But Shepard never got to realize his dreams. Just after midnight on October 7, 1998, when Shepard was a 21-year-old college student, two men lured him to a field outside Laramie. They viciously beat him, tied him to a fence, and left him in the freezing cold. Why? Because Matthew Shepard was gay.

From an early age, Matthew Shepard was on a mission to make a difference in the world. At just 7 years old, he volunteered for an environmental group. The group was working to get his hometown of Casper, Wyoming, to start a recycling program. In the sixth grade, he played Abraham Lincoln, his role model, in a school play. And in high school, he was elected as a peer counselor. That was because he was committed to helping others.

Shepard was also passionate about international human rights. That interest eventually led him to study political science at the University of Wyoming in the city of Laramie. He hoped to one day work for the U.S. State Department. There, he could devote his life to helping people in other countries gain the same opportunities that he had in the United States.

But Shepard never got to realize his dreams. When he was a 21-year-old college student, two men lured him to a field outside Laramie. It was just after midnight on October 7, 1998. The men viciously beat him and tied him to a fence. They left him there in the freezing cold. Why? Because Matthew Shepard was gay.