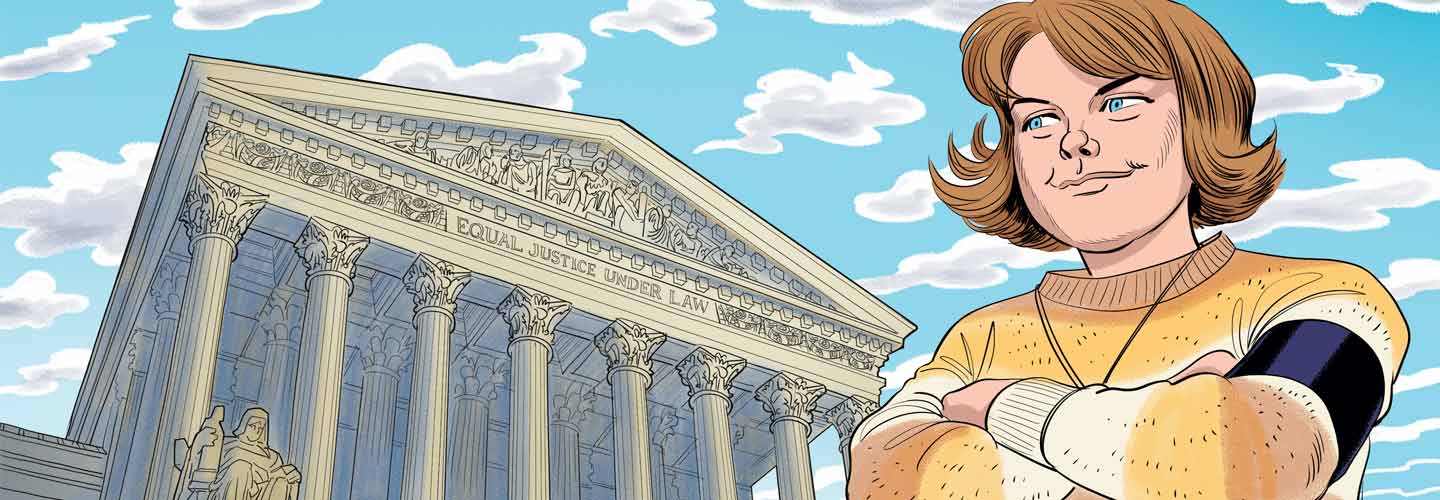

When it comes to our nation’s existing laws, who has the most influence? It’s not the president or even Congress—it’s the U.S. Supreme Court!

The Supreme Court is the nation’s highest court. Its nine members, called justices, have the final say on whether laws and government regulations are constitutional—meaning permitted under the U.S. Constitution. If the Court determines that a law is unconstitutional, it must be changed or repealed.

The Court is asked to hear approximately 8,000 cases each term—which lasts from October to June—but accepts only about 80. The justices take on cases that will affect people nationwide, not just those involved in the case. Justices listen to arguments from lawyers on both sides of the issue, then make their ruling. The decisions the Court makes have a lasting impact on the nation’s laws and the lives of Americans.

When it comes to our nation’s existing laws, who has the most influence? It is not the president or even Congress. It is the U.S. Supreme Court!

The Supreme Court is the nation’s highest court. Its nine members are called justices. They have the final say on whether laws and government regulations are constitutional. This means allowed under the U.S. Constitution. If the Court determines that a law is unconstitutional, that law must be changed or repealed.

The Court’s term lasts from October to June. The Court is asked to hear about 8,000 cases each term, but it accepts only about 80. The justices take on cases that will affect people nationwide, not just those involved in the case. Justices listen to arguments from lawyers on both sides of the issue. Then they make their ruling. The decisions the Court makes have a lasting impact on the nation’s laws and the lives of Americans.